Aaron

Sorkin "can't handle the truth!"

the actual final

decision of US Patent Office

Interference #64,027

Farnsworth -v- Zworykin - TELEVISION SYSTEM - July 22,1935

--the new Broadway play reverses the

verdict!

|

The story of how television arrived in this world is

one of the most compelling sagas of the past century. It's about

time somebody turned it into popular entertainment, and there is

really nobody more qualified to do so than Aaron Sorkin, creator

of The West Wing and A Few Good Men, among other

things. When the play finally opens at the Music Box Theater on

45th St. in New York, its arrival will culminate a creative odyssey

that has taken almost as long to reach the stage as it took television

itself to emerge from the laboratory in the 1930s and enter the

cultural firmament. |

|

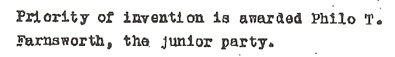

The Farnsworth Invention is an ambitious undertaking in which playwright Sorkin aspires to cast himself alongside such theatrical landmarks as Robert Bolt's A Man for All Seasons or Peter Shaffer's Amadeus. But The Farnsworth Invention falls sadly short of its loftiest ambitions for the simple reason that it is not faithful to its underlying history. If Bolt and Shaffer had followed the examples set here, then Sir Thomas More would have lived rather than losing his head to an axe, or a royal court might have assigned credit to Antonio Salieri for writing all of Mozart's symphonies and concertos. The problem with The Farnsworth Invention is that it arrives at a conclusion that is contrary to the facts. In its climactic scene, a patent court judge says, "priority of invention is awarded to Vladimir Zworykin" -- the engineer who developed television for RCA. For an audience that by the end of the second act has come to think it is viewing a reliable re-enactment of actual events, this statement does irreperable, almost violent harm to the truth: In the litigatation portrayed in this scene, the final decision, delivered in 1935, actually read "priority of invention is awarded to Philo T. Farnsworth" -- the prodigal genius of the play's title. The great mystery here is why Aaron Sorkin -- the man who wrote Jack Nicholson's final speech in A Few Good Men -- "can't handle the truth." The play's a initial adherence to the actual facts is seductive: First, we are introduced to Philo T. Farnsworth, a precocious teenager seemingly sent to this earth with special gifts that are manifest in an invention that would truly change the world. Farnsworth's story is interwoven with that of David Sarnoff, the ruthless and singleminded -- some might say "visionary" -- president of the Radio Corporation of America, who was determined that his company alone would be responsible for adding "sight to sound." In the first act, anybody familiar with the story will be impressed by how well the play follows the course of actual events. Sure, things are compressed and transposed, and composite characters are introduced. But the essence of those events is effectively conveyed: We meet the young genius and learn of his novel idea; At the same time, we can see the titanic forces that are marshalling on the horizon that would challenge and ultimately impede the young prodigy's promise. And all of this is conveyed with the kind of dense-but-snappy dialog that Aaron Sorkin is renown for, along with a rich sprinkling of surprising humor. Mr. Sorkin said once that he was in neither the Farnsworth nor the Sarnoff camp: "I just hope the jokes work," he said, and judging from the audience response they do. The first act is lively, informative, and engaging enough to lull the the audience into believing that what follows is a reliable portrayal of actual events. But ultimately, this is entertainment that betrays its history lesson, and Mr. Sorkin's assertion that he is in neither "camp" is belied in the way the play perpetuates RCA's own half-century-plus of revisionist "spin." . In the second act, the underlying issues become more complex, and the play begins to come loose from its historical moorings. By the time it reaches its dramatic "courtroom" climax, the premise is ungrounded and the conclusion, sadly, crosses a line from acceptable "dramatic license" to an outright reversal of the historical record. And if that's not bad enough, the final moments leave the audience with the impression that Farnsworth was "sad and desperate" -- as one viewer put it -- unless they take the time to seek a better understanding of the source material. To that end, we offer this website, with a scene-by-scene synopsis of the play, comparing each scene against the historical record. Aside from its historical revisions,, The Farnsworth Invention is an impressive production. The performances of the two principle actors -- relative newcomer Jimmi Simpson as Philo T. Farsworth and stage-and-screen veteran Hank Azaria as David Sarnoff -- are thoroughly convincing. They all deserve their standing ovations. Simpson, in particular, is so engaging on stage that this event surely marks the arrival of a new star on the show-biz firmament. The staging is complex but artful, and director Des McAnuff and his large cast of supporting players have much to be proud of. And lord only knows what all is going on backstage as actors and actresses change costumes and wigs and go on and off stage in a variety of ensemble roles. Hey, it's a good time at the theater. We fully understand that history is not necessarily

drama, and that audiences come to the theater first and foremost

to be entertained. But where historical drama is concerned, a

theatrical (or cinematic) experience is most effective when the

action on stage is an accurate reflection of the actual facts.

The Farnsworth Invention is such a production, and the pages that follow will attempt to answer some of those questions for you. START HERE. |