|

The Farnsworth

Invention: Fact -v- Fiction

|

|

Act I, Scene 7: In which the red herring is thrown into the stew |

| The Play |

The Facts

|

|

| We're back to Dempsey -v- Carpentier. Dempsey wins in a "late round knockout" | Actually the fight was stopped on a TKO in the 4th round. But it was the "Fight of the Century" and the first ever to generate a million-dollar gate -- and a broadcast audience in the hundreds of thousands. |  Dempsey had Carpentier on the ropes by the third round |

In an narrative exchange between the Sarnoff and Farnsworth, Sarnoff asserts that the picture Farnsworth had attained is of "no practical value" because "it needed too much light." When Farnsworth counters that Zworykin didn't have a picture at all, Sarnoff says "he solved your light problem and filed a patent four years earlier." |

The play doesn't exactly go off the rails here, but it's starting to wobble. The introduction of the "light problem" is a red herring, one of the issues promoted over the years by RCA to make a case for its own belated -- and nominal -- contributions to the art. What the play fails to assert effectively is that Farnsworth's invention "proved the principle' of electrical scanning, thus paving the way for all future improvements. Considering the mechanical contraptions that preceded it, Farnsworth's system was a breakthrough of epic proportions, the innovation that spawned an entire industry. Yes, in the early days there were issues of light sensitivity, but Farnsworth was responsible for just as many innovations that solved that problem as any other engineer or laboratory. |

Another photo from the 1928 SF Chronicle article, showing an already well advanced Image Dissector tube |

| Sarnoff resumes railing against AT&T's selling advertising on its radio station while continuing to plan for the Dempsey - Carpentier fight. He begins ruminating over the formation of a new company to specialize in broadcasting. | Another compression of actual events. One minute they're talking about an event that took place in 1921; in the next breath, they're creating the National Broadcasting Company, which transpired in 1926. | |

| James Harbord, President of RCA, asks Sarnoff why the rivalry with Walter Gifford, President of AT&T? There may be something personal at the root of it, but Sarnoff insists it's just business, and that AT&T will have to get out of the radio business. | There was considerable personal enmity between Sarnoff and Gifford. At the root of their business rivalry, Sarnoff considered broadcasting to be the exclusive domain of RCA under the patent-pooling arrangements. On a more personal level Gifford is on record as having called Sarnoff "abrasive" and "Jewish." |  AT&T President Walter Gifford ca. 1927 |

Sarnoff tells Harbord he wants to buy the Audion Tube, and a discussion ensues re: the cost benefits of such a transaction. Sarnoff justifies the proposition with the suggestion that "RCA shouldn't be be paying patent royalties, we should be collecting them." |

The paternity of the Audion Tube (the basic, three-element amplifier/rectifier that made broadcasting possible) and its underlying circuits -- and the patent litigation around those issues -- are among the most complex and arcane issues in the history of radio. However, the issue of patent ownership -v- licensing is really the issue at the very heart of this particular drama. Sarnoff's statement that RCA 'should' be collecting royalties instead of paying them was in fact an iron-clad policy that prevented RCA from doing business with Farnsworth (or anybody, for that matter) on reasonable terms. |

|

| Jim Harbord announces that he is leaving RCA to take a position with Herbert Hoover, and Sarnoff is elevated to the post of president of RCA. | Sarnoff served as Vice President and General Manager of RCA in 1922; in 1929 he was promoted to Executive Vice President. He was promoted to President of RCA on January 3, 1930. |  James Harbord names David Sarnoff president of RCA - January 3, 1930 |

Sarnoff takes lunch with Walter Gifford, his rival at AT&T. RCA now controls the Audion tube, which Sarnoff uses as leverage in his negotiations with Gifford. Sarnoff wants AT&T out of the broadcasting business.

|

Both RCA and AT&T were subject to federal scrutiny for their monopolistic practices. In 1926, a compromise was arranged by Owen Young, the Chairman of RCA, whereby AT&T surrendered its broadcasting interests to RCA in exchange for exclusive right to connect by wire the many radio stations that would form a new network, the National Broadcasting Company. The formation of NBC was both a victory and a defeat for Sarnoff, who would have to rely on advertising to make the new company self-sufficient. |

Owen D. Young, the founder and first chairman of RCA |

| Back in narrator mode, Farnsworth enumerates Sarnoff's next moves... buying the Audion tube and "bought the frequency modulation band from the great Edwin Amstrong..." | RCA did wrap the Audion tube into its patent portfolio, and also controlled the heterodyne and super heterodyne circuits, invented by Edwin Armstrong, which are fundamental to radio broadcasting. However, the battle over "frequency modulation" -- FM -- was another epic struggle in which Sarnoff tried to crush a brilliant inventor who dared to stand in the path of Sarnoff's quest for Global Domination.

|

Edwin Armstrong introduced static-free FM radio in 1935. RCA appropriated the technology to use for the audio portion of television transmissions. |

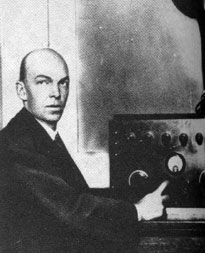

| The storylines begin to merge when Sarnoff obtains a copy of the San Francisco Chronicle from September, 1928. Somebody named Philo T. Farnsworth has produced an all-electronic television signal, which of course Zworykin has been saying can't be done. | Zworykin was introduced to the idea of electronic (i.e. cathode-ray) television under the tutelage of his professor in Russia, Boris Rosing. He never said it couldn't be done, he just didn't quite know how to do it -- until Philo Farnsworth showed him the way. | |

| Again, a mention of the "very weak signal" from Farnsworth's Image Dissector. | The play hinges its dramatic turn on Farnsworth's "very serious light problems," implying ultimately that Farnsworth had no solution to this simple "engineering" issue. Actually, many -- if not most -- of the improvements to the first system that found their way into television cameras in the 1940s and 50s started as innovations in Farnsworth's lab. |

Farnsworth invented the first "film chain" and used motion pictures via television to refine his system. |

| His aides suggest Sarnoff "make an offer" of $100,000 for Farnsworth's patents. Sarnoff brushes the suggestion off, since that would me that Farnsworth, rather than RCA, had invented television. | In 1930, David Sarnoff visited Farnsworth's laboratory in San Francisco while Farnsworth was not there. After seeing real television for the first time, he offered $100,000 to George Everson for the whole enterprise. When Everson refused, Sarnoff stormed out saying "then there is nothing here we will need." |  Farnsworth poses with a 1929 prototype home receiver. |

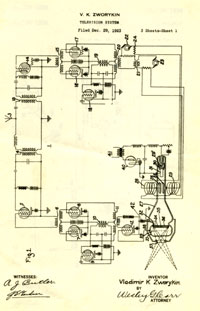

| Sarnoff asks "if Zworykin can get a good picture... can he revisit his 1923 patent application and seek priority of invention..." | Zworykin applied for a patent for an electronic television system in 1923, but as of 1930 (and beyond) the actual patent remained un issued, as is typically the case with inventions that cannot be "reduced to practice" -- i.e. made to work. But the suggestion that Sarnoff/RCA saw merit in Zworykin's un issued patent is valid, and the words "priority of invention" will prove important in both the play and the history -- though for different reasons. |

Illustrations from Vladimir K. Zworykin's 1923 patent application |

| Sarnoff increases Zworykin's budget for television research to $200,000. | It is important to note that Zworykin was still employed at Westinghouse, in Pittsburgh PA, when Sarnoff learned of Farnsworth's developments. In 1929, Sarnoff met with Zworykin and offered underwrite his work, but Zworykin remained under Westinghouse's roof until the middle of 1930. |

NBC and RCA engineers were still experimenting with mechanical television systems as late as 1929 |

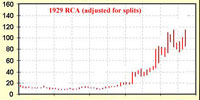

| Act I ends with the stock of RCA shooting above $100 per share. Sarnoff speculates that his company's share price is probably headed for "an adjustment." | The finance industry's term for the drop in a company's stock after a sharp run-up is "correction." |  By October 1929, RCA's stock price had risen to $118/share |

Want the whole story? Read a Book! |

The Boy Who Invented Television A Story of Inspiration, Persistence, and Quiet Passion by Paul Schatzkin |

|