|

The Farnsworth

Invention: Fact -v- Fiction

|

|

Act II, Scene 7: In which that which was truly lost is revealed |

| The Play |

The Facts

|

|

| Sarnoff says the outcome of the litigation didn't really matter, that all he had to do was 'run down the clock' on the 17 year life of Farnsworth patents. | This is a common misconception. Yes, patents last 17 years, but their life is extended for as long as they are contested. And new patents, like those covering the Image Orthicon, bore a later inception date and so would last well beyond the extended life of the original patents. And more importantly, rather than waiting for those patents to expire, RCA paid Farnsworth at least $1-million for a license to use them. | |

| ...and that was easy, since there was a war brewing... | Farnsworth retreated from all things television after setting up his new company in Fort Wayne. By 1940, he was comfortably ensconced on a private retreat in Maine. |  Fernworth Farm |

| The play now imagines a scene where Farnsworth and Sarnoff are "left alone." They discuss a wide range of topics. Sarnoff offers Farnsworth a job at RCA. "Why," Farnsworth replies, "so that you can tell me what to invent next" ? | It is glossed over in this scene, but THAT is really the central issue in the life of Philo T. Farnsworth. His was the kind of intellect that needed free reign, not bureaucratic management. His struggle was to preserve the golden goose by licensing his patents, rather than killing it by selling them. | |

| Farnsworth laments, "I just lost television.... the billion dollars I'm not going to get might have come in handy..." | Indeed. The record clearly shows that Philo T. Farnsworth invented a little thing called television. The proceeds from the patents for that invention should have generated should have given him the wherewithal to invent whatever he put his mind to for the rest of his life. | |

| Sarnoff asks Farnsworth what he's gonna do. Farnsworth says something about "fusion." | In 1953, Philo Farnsworth conceived an approach to nuclear fusion, the process within the stars that offers the promise of clean, safe, and abundant energy if it can ever be harnessed here on earth. In 1959 he built the first prototypes of his "Fusor" and set out to prove the principle. Using the analogy of his early television work, his family was asked once if he had produced the equivalent of that principle-proving 'first picture' in 1927. "Yes," came the answer, "he got that first picture." But because of the way his business went, he lacked the resources to take his work to full fruition. |

The first Farnsworth Fusor, ca. 1959 |

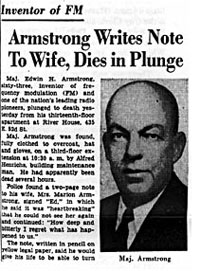

| Farnsworth asks why Edwin Armstrong killed himself. | As noted earlier, Armstrong invented Frequency Modulation radio -- FM -- and then fought bitterly with RCA over the patents. Armstrong was motivated in part by Farnsworth's victories, certain that he could replicate that success. Likewise, Sarnoff was determined that RCA would not lose such a case again. The stand-off ended in 1954 after Armstrong stepped out the 14th floor window of his Manhattan apartment, and RCA reached a settlement with his widow. |  |

| In his concluding soliloquy, Sarnoff says that Farnsworth was hospitalized in 1949 for depression. | Farnsworth did suffer bouts of depression at different times in his life. He did have something of a "nervous breakdown" in 1940 just before retreating to his farm in Maine. And there were times when he self-medicated with alcohol. But in 1949, he returned to Fort Wayne and tried desperately to salvage the company that bore his name. Farnsworth Television and Radio had fared well on military contracts during the war, but faltered just as television was beginning to sweep the country -- powered the Image Orthicon tube that was largely his invention. In 1949 Farnsworth Television and Radio was sold to ITT corporation, and ITT entered a cross license with RCA that got Farnsworth out of the television business once and for all. |

|

| Sarnoff continues: "He lived another twenty-five years after that, but he died drunk, and broke, and in obscurity." | It is ironic to hear that Farnsworth died "in obscurity" -- coming from the principle architect of that obscurity. Farnsworth died in 1971 of pulmonary failure. The play could have just as well have said that "before he died, Phil and Pem were married in the Mormon Temple, in a ceremony intended to assure their eternal union in the after life. But he died of a broken heart...." |

Phil and Pem after their temple wedding |

| Sarnoff tells a joke about Pete Conrad leaving the surface of the moon. | It's sorta bizarre that the biggest laugh in the whole show is not original. It's an old "urban legend" about something Neil Armstrong said just after "One small step for man.." | |

| Sarnoff confesses, "he deserved better in my hands..." and then justifies his actions by saying "I burned his house down so he wouldn't burn mine down first." |

The play is reaching for its thematic wrap up here. It's unfortunate that the theme is not based on anything that actually happened. Philo Farnsworth was never going to burn David Sarnoff's house down. To the contrary, they could have built a glorious mansion together. But Sarnoff would not be satisfied with anything less than the grandest palace in the land, and for that, he had to steam roll everything in his path, including the one man who could have built the foundation and walls for him. Sarnoff was just not willing to pay a fair price. He was only willing, as the play says, to steal it, "fair and square." And so we are supposed to believe, as Sarnoff says at the of the play, that "the ends justify the means" because "that's what means are for." Funny line. Only now do we see how tragic, also. |

|

| In the final moments, Farnsworth is shown -- in a bar, again! -- on July 16, 1969 watching the Apollo 11 lift-off while scribbling schematics of his fusion ideas. He wishes the crew "Godspeed, fellas," as the launch counts down. | In real life: Phil and Pem sat in their living room in Salt Lake City on July 20, 1969, watching along with half-a-billion other people -- a planet unified, if only for a moment, by the Farnsworth invention. As the camera came out of the side of the Lunar Module and focused on Neil Armstrong, as Armstrong stepped off the LEM in a ghostly image seen around the world, Philo T. Farnsworth turned to his wife and said, "Pem, this has made it all worthwhile." |

|

|

||

Want the whole story? Read a Book! |

The Boy Who Invented Television A Story of Inspiration, Persistence, and Quiet Passion by Paul Schatzkin |

|